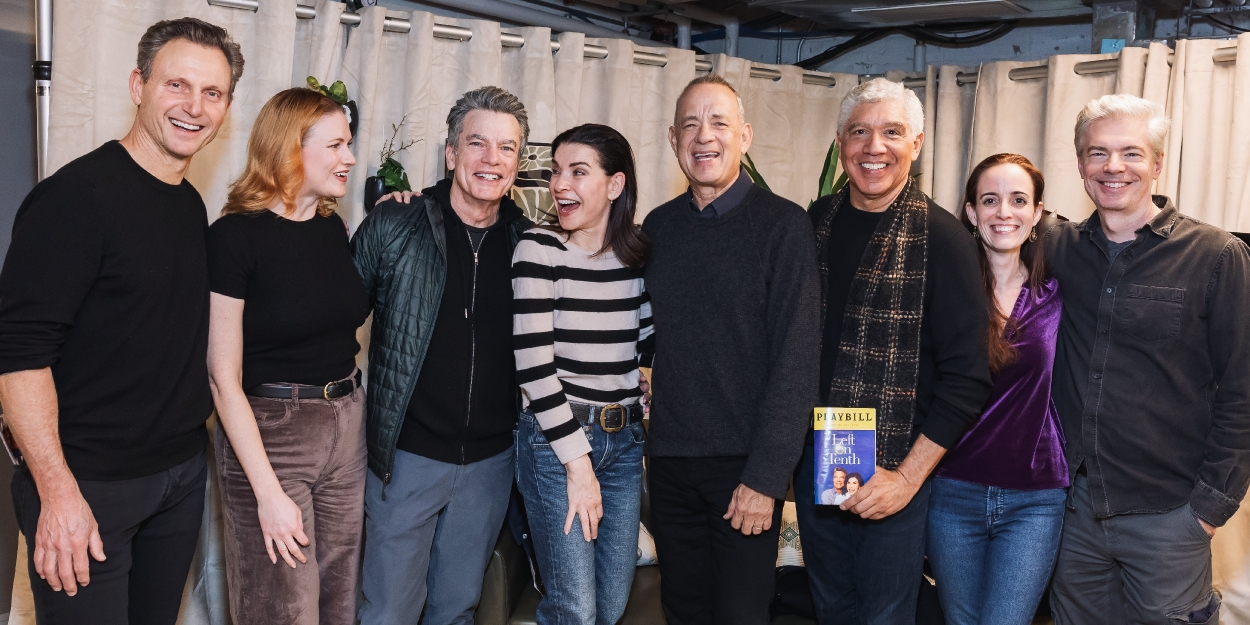

Enrique Galan (Angel Cruz) and Linda Mendivel (Mary Jane Hanrahan) / Photos by Leesa Richards

By Aaron Krause

During a riveting South Florida professional production of the gripping play, Jesus Hopped the A Train, prisoner Angel Cruz (Enrique Galan) presents his arms for cuffing. But look closer; note the deeply repentant expression on his face and the aching vulnerability escaping Cruz’s voice. Is the inmate also begging the jailer, Valdez (Ricky J. Martinez) to hug him or, at the very least, requesting a reassuring pat on the shoulder?

You may ask such questions while experiencing the Marshall L. Davis Sr. African Heritage Cultural Arts Center’s moving, intense, and believable production of Stephen Adly Guirgis’s fierce drama. The roughly two-hour-and-15-minute production (including a 10-minute intermission) continues through Oct. 20 in the center’s intimate Wendell A. Narcisse Performing Arts Theater in Miami.

A talented cast presents a master class in naturalistic acting even during the most intense moments. In fact, the actors disappear into their characters under Teddy Harrell Jr.’s sensitive direction, smart staging and deft pacing. In addition to Galan and Martinez, the cast includes Linda Mendivel, Jean Hyppolite, and Demitri Narace.

Credit also behind the scenes artists Michael “MIK” Miles (scenery), Quanikqua “Q” Bradshaw-Bryant (lighting), James Mungin II (sound), and Jacquelin Hodge (costumes) for their fine work.

Without question, Jesus Hopped the A Train is a play intended for mature adults. Indeed, the piece features frequent filthy language that you wouldn’t want children to hear. But Guirgis’s gritty, vulgar, darkly comical dialogue sings. Call it provocative, profane poetry, as masterful as some of David Mamet’s famously coarse and clipped dialogue dubbed “Mamet Speak.”

Clearly, Guirgis possesses a keen ear for dialogue from the rough and tumble streets. Also, without condoning their behavior, the playwright paints vivid, sympathetic portraits of people from whom we may choose to keep a far distance. But to meet Guirgis’s characters is to experience an exercise in empathy or at least sympathy. The writer, whose prose leaps off the page and stage, displays a deep compassion for the troublemakers in society. Guirgis doesn’t pretend to condone their behavior, but clearly believes redemption and even change is within their reach, given the right influences.

Still, we all have our limits on how far we can bend before our wells of sympathy and empathy dry up. And chances are, you will reach that breaking point at least once in Jesus Hopped the A Train. There are some things that we simply cannot condone.

In the play, Cruz is a Harlem man from Puerto Rico accused of attempted murder for shooting Reverend Kim, a spiritual cult-like leader and offstage character claiming to be the Son of God. Actually, Cruz admits to his lawyer, Mary Jane (Mendivel) that he shot Kim in the butt. Cruz insists that he did it to rescue his friend (also an offstage character) from Kim’s abusive cult, and that he wasn’t trying to kill Kim. Against her better judgement, Mary Jane decides to not only defend Cruz but aim for acquitting the defendant. t’s interesting that the playwright gave Cruz the first name Angel; certainly, he is no angel, and he surely doesn’t believe in celestial beings.

Authorities transfer Cruz to protective custody in a 23-hour lockdown wing on New York City’s Rikers Island after prisoners assault him at another facility (we never witness the assault but notice Cruz’s beat-up face). While at the extra-secure facility, Cruz meets another inmate, an African American man named Lucius Jenkins (Hyppolite).

Jenkins is a serial killer and born-again Christian whose charisma and charm will win you over before you learn about at least one of his shocking crimes. Possibly, it will make you sick to your stomach.

Jenkins has won over correctional officer D’Amico (Narace) who seems nice and somewhat of a pushover. But after the boss dismisses D’Amico for an unknown reason, Valdez takes over. He proves to be a sadistic guard who doesn’t take any crap from inmates. As a matter of fact, he seems like one of the bad guys.

Demitri Narace (D’Amico)

But from your first encounter with Jenkins, you would never guess that he has committed shocking crimes. How in the world, you may ask, did Jenkins go from killing eight people to becoming a God-adoring, seemingly serene and happy individual wishing to spread the good news of the Lord to others. In particular, Jenkins aims to convert newly-arrived nonbeliever Cruz. Will Jenkins reach Cruz before it’s too late? What difference exists (if any) between Reverend Kim’s evangelizing efforts and Jenkins’ proselytizing attempts?

In this layered play, Guirgis, without spoon-feeding us answers, raises complex questions about race, class, ethics, religion, faith, and the legal and criminal justice system. Undoubtedly, audiences will have much to ponder after the curtain comes down.

Jesus Hopped the A Train is sophisticated without talking down to audiences and passionate without becoming sentimental or too melodramatic.

On the downside, the play contains clunky exposition, including details that seem irrelevant to the narrative. Do we really need to know, for instance, that Valdez used to be a city sanitation employee before becoming a corrections officer? Also, it is never clear what exactly happened to Cruz’s friend, Joey, an offstage character taken under Reverend Kim’s wing. In addition, at one point, the play awkwardly moves between the present and the past in such a way that in one scene, we think we’re seeing and hearing a dead person. Finally, we learn that at some point in his life, Jenkins detested sunlight, but we never learn why.

Jesus Hopped the A Train, which takes its title from an incident during Cruz’s childhood, alternates between intense, fast-paced moments of snappy dialogue and long monologues. These speeches not only (mostly) reveal relevant information but also offer performers moments to truly shine in the spotlight.

Speaking of performing, the five-member cast mostly excels. However, there are moments when they need to project more or at least wear microphones. In an effort to appear truly natural, actors can sometimes speak too softly for live theater, whereas in film or television, microphones can pick up their voices.

Hyppolite delivers a tireless, tour-de-force performance as the overly talkative Jenkins, whose loud mouth seems to be in perpetual motion.

Some of Jenkins’ lines could trip up less experienced performers. However, Hyppolite, a Miami native, seasoned performer, and theater manager at the African cultural center, never misses a beat. At one point, Jenkins delivers a monologue while working out. During the speech, the character quickly mentions the books of the Bible backwards. Certainly, portraying Jenkins tests an actor’s stamina, but the soft-spoken, seemingly modest Hyppolite nails the challenge.

Appearing relaxed, his dark eyes shining, and beads of sweat appearing on his forehead, Hyppolite talks with his entire body, including his arms, which move loosely as his character extols the Lord or even tries to calm Cruz. But Hyppolite also transitions seamlessly to moments of tension when his body tenses and strain as well as pain creeps into his voice.

Galan, a Miami-native and versatile performer who somewhat resembles actor Adrian Brody, credibly imbues Cruz with a demeanor that combines weariness, frustration, desperation, and sadness. Galan, sporting tattoos, possesses expressive eyebrows and dark eyes. You notice them as soon as you first see him on stage. Galan’s telling facial expressions combine with his expressive voice to create a believable, sympathetic character even if we don’t condone all his actions. Galan’s Cruz at times looks at Jenkins, and then looks away, suggesting that the talkative prisoner grabs his attention, but at other times, bores or sickens him.

Rickey J. Martinez (Valdez)

Martinez, a versatile theater artist well-known in Miami, portrays Valdez in such a way that you sense the guard truly relishes each and every chance to mock and torment his prisoners. Call his approach playful and merciless mocking menace. Sarcasm and menace gush from Martinez like lava from a fast-moving volcano. But Martinez, with a shaved head, raised eyebrows, and expressive eyes, is also believable during his character’s rare moment of subdued sympathy toward the end.

Mendivel, a New York native and an alumna of the prestigious William Esper Studio, convincingly lends lawyer Mary Jane determination and a business-like demeanor that suggests the attorney takes her job seriously. In addition, during a monologue, Mendivel speaks about her character’s past with a familiarity that suggests she remembers her childhood clearly.

As D’Amico, Narace lends his character an affable aura in the beginning and later, endows his speech with the right amount of somberness.

Miles’ scenic design consists mostly of fences and a properly somber-colored backdrop, befitting the play’s seriousness. But there is an openness to the scenic design; you don’t get a claustrophobic sense that the lock-down wing is enclosed. This could serve as negative criticism, but the scenic design’s openness can also be symbolic in a way that works for the play. After all, the piece criticizes our system of justice. Specifically, the set’s openness could symbolically suggest that there is a gap in our criminal justice system that fails society. Another way to look at Miles’ set design is that it suggests an enclosed facility but asks audience members to use their imagination to fill in the blanks.

Also behind the scenes, Bryant’s shifts in lighting intensity mark transitions from realistic scenes to those in which characters deliver monologues to the audience. The designer’s use of the color red is also proper for at least one scene.

In the costume department, designer Hodge’s outfits resemble real prison jumpsuits. Also, the darker colors the designer uses for characters who are not inmates (such as the lawyer) befits the seriousness of this play.

Mungin’s sound design creates realistic effects of appropriate noises such as prison cell doors slamming shut.

When doors metaphorically close in our lives and we no longer have something that we once took for granted, we miss it sometimes. This is hardly a revelation, but we can credit Jenkins for reminding us to appreciate simple things in life such as sunlight.

Jenkins can certainly win you over and charm you. But again, once you learn about the sickening nature of one of his crimes, you want to harm the character. And as Hyppolite’s Jenkins casually, even joyfully describes his heinous act, you have to stop yourself from charging the stage. Some people, such as Jenkins, are just masterful at hiding their dark side.

Jesus Hopped The A Train through Oct. 20 from the Marshall L. Davis Sr. African Heritage Cultural Arts Center, 6161 N.W. 22nd Ave. in Miami. For tickets go to https://ahcamiami.org or call (305) 638-6771