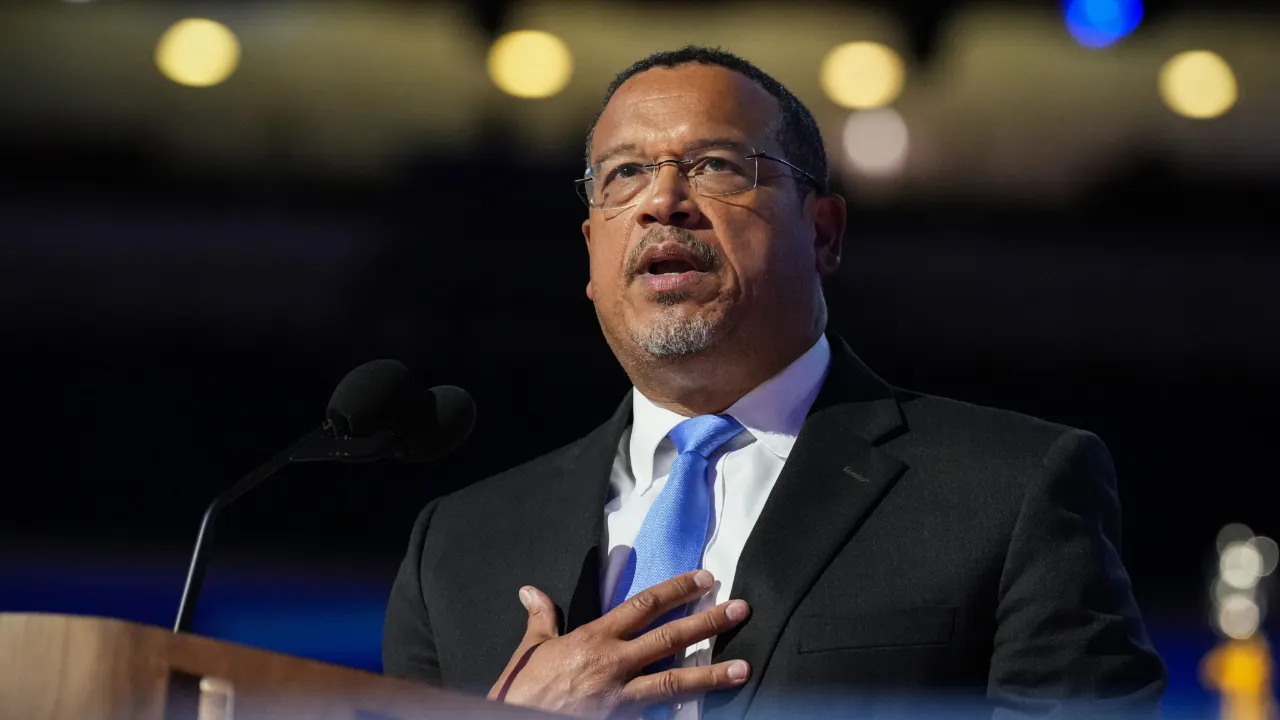

Washington — The Supreme Court is hearing arguments over whether President Trump can fire Lisa Cook from her post on the Federal Reserve Board of Governors.

Mr. Trump moved to oust Cook last August over allegations she engaged in mortgage fraud. A senior official in his administration, Federal Housing Director Bill Pulte, had claimed that Cook made misrepresentations on mortgage documents relating to properties in Michigan and Atlanta, Georgia.

The Federal Reserve Act of 1913 allows the president to remove a member of the Fed’s Board of Governors “for cause,” though the law does not define the term. In informing Cook of her removal, Mr. Trump wrote in a letter shared to social media that he had “sufficient cause” to do so because of what he claimed was “deceitful and potentially criminal conduct in a financial matter.”

Cook has denied wrongdoing and has not been criminally charged. Mr. Trump’s move to fire her was unprecedented. No other president has tried to oust a Fed governor in the central bank’s 112-year history.

Oral arguments

Solicitor General D. John Sauer told the justices that “deceit or gross negligence” by a financial regulator is cause for removal, and said the president has discretion to oust an officer for reasons related to her conduct, ability, fitness or competence. He argued that allowing Cook to remain in her position while her case proceeds would do “grievous injury” to the public’s perceptions of the Fed.

“The American people should not have their interest rates determined by someone who is at best grossly negligent,” he said.

Several of the justices pressed Sauer about the consequences of a decision allowing Mr. Trump to fire Cook, and specifically the ramifications for the U.S. economy. Justice Amy Coney Barrett pointed to predictions from economists that Cook’s removal could trigger a recession.

“How should we think about the public interest in a case like this?” she said, later adding that the risks to the economy may counsel caution by the Supreme Court.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh pushed Sauer on the implications of the administration’s position in the case and how it would impact the Fed’s independence.

“Your position that there’s no judicial review, no process required, no remedy available, very low bar for cause that the president alone determines — that would weaken if not shatter the independence of the Federal Reserve,” he said.

Kavanaugh said that if the Supreme Court accepts Mr. Trump’s view, a Democratic successor could come in and fire all of his appointees, effectively turning the Fed’s for-cause removal standard into at-will. Kavanaugh, who was appointed by Mr. Trump, stressed that the court should think about the “consequences of your position for the structure of the government.”

“It incentives a president to come up with what, as the Federal Reserve former governors say, trivial or inconsequential or old allegations that are very difficult to disprove. It incentivizes kind of the search-and-destroy and find something and just put that on a piece of paper,” he said. “No judicial review. No process, you’re done.”

Cook’s case

Al Drago / Bloomberg via Getty Images

Cook sued over her removal last year, arguing that the president violated the Federal Reserve Act. She also said she was entitled to and deprived of notice and the opportunity to a hearing before she was fired.

U.S. District Judge Jia Cobb sided with Cook and reinstated her to her post, finding that Mr. Trump had not validly removed her “for cause.” The judge also ruled that Cook was likely to succeed on her argument that she was deprived of her due-process rights because she did not receive the necessary process before her firing.

A divided panel of three appeals court judges continued to block Cook’s removal, and the Trump administration sought emergency relief from Supreme Court and asked the justices to allow the president to oust her.

The high court has allowed Cook to remain in her position while it considers whether Mr. Trump can fire her and is hearing the case on an expedited schedule. Cook has participated in the last two meetings of the Fed’s interest-rate-setting committee. Its next meeting is set for later this month.

The dispute involving Cook’s firing poses a test for the independence of the Fed, which defenders of the bank argue would be jeopardized if the Supreme Court rules for Mr. Trump. Arguments also come days after Fed Chairman Jerome Powell revealed the central bank received criminal subpoenas from the Justice Department stemming from a criminal investigation into him.

The Supreme Court has allowed Mr. Trump to fire members of other independent agencies and appears poised to overturn a 90-year-old decision that allowed Congress to impose removal protections for officials at multi-member boards and commissions. But it has also signaled that it views the Fed differently from those other entities.

In May, the Supreme Court singled out the Fed as a “a uniquely structured, quasi-private entity that follows in the distinct historical tradition of the First and Second Banks of the United States.” Justice Brett Kavanaugh separately suggested in December that the court could create an exception for the central bank to the president’s otherwise unrestricted power to remove certain executive officers.

Unlike the case involving removal restrictions for independent agencies, the Justice Department is not challenging the constitutionality of the Fed’s for-cause protection. Instead, the key issues are whether Mr. Trump needed to give Cook notice and a hearing before removing her, if the president had cause to fire her — and what constitutes “cause” — and whether courts can review that decision.

Sauer argued in Supreme Court filings that the president lawfully ousted Cook after “concluding that the American people should not have their interest rates determined by someone who made misrepresentations material to her mortgage rates that appear to have been grossly negligent at best and fraudulent at worst.”

Cook’s alleged conduct “created an intolerable appearance of impropriety in someone charged with the weightiest responsibilities in our financial system,” he wrote. “There is a world of difference between that removal and removals grounded in policy disagreements.”

Sauer also told the justices in papers that courts cannot second-guess the president’s determination that there was cause to fire Cook. But even if they could, Mr. Trump identified a valid reason for doing so: her “apparent fraud or gross negligence in a financial matter,” the solicitor general said.

Cook’s lawyers called the allegations against her “flimsy” and “unproven” and argued in papers that the Fed’s independence and removal restriction prohibit her firing. They said that allegations of private, pre-office conduct do not constitute “cause” for removal under the law. Cook joined the Fed Board in May 2022, and the allegations involve mortgage agreements from 2021.

Cook also did not receive the notice and opportunity to be heard that she is due under federal law and the Constitution’s Fifth Amendment, they said. Her lawyers warned that accepting Mr. Trump’s argument that removals from the Fed Board are not subject to judicial scrutiny would “eviscerate” Congress’ choice to protect the central bank’s independence.

“Congress did not mean for the nation’s monetary policy to turn on that game of find-an-alleged crime,” they said.

Mr. Trump has frequently expressed frustration with the Fed and Powell over decisions regarding interest rates. He has denounced the chair as “incompetent” or “crooked.”

Powell and Cook have separately suggested that the accusations leveled against them are pretextual, and indicated Mr. Trump is targeting them for disagreements over monetary policy.