Independent political analyst Asrul Hadi Abdullah Sani told CNA that Malaysia’s policy U-turns over the years have eroded public confidence in the government and led to a lack of trust in federal programmes and policies.

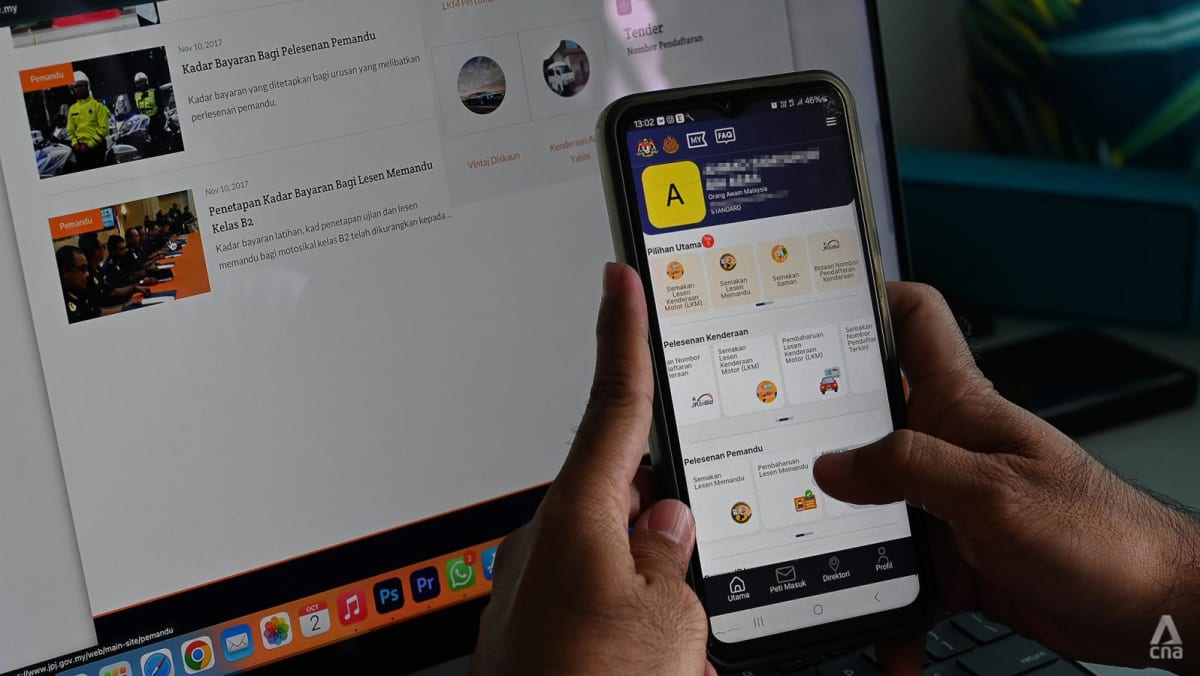

This could be seen in the “low number” of registrations for PADU, he said, referring to Malaysia’s central data hub aimed at collecting detailed income data of all Malaysians to allow the precise targeting of government subsidies.

The government initially set a goal of getting 29 million Malaysians to voluntarily register for PADU by a Mar 31 deadline. But a slow rate of sign-ups, compounded by cybersecurity concerns and claims of a trust deficit, compelled the government to lower its target to 11 million, or half of Malaysia’s adult population.

After registration closed on Mar 31, PADU’s total enrollment including children stood at 17.65 million, reported the Malay Mail.

“The recent policy reversals, such as MyDigital ID and others, are reinforcing the public’s perception that the Anwar administration is not different from previous governments,” Mr Asrul Hadi added.

During the COVID-19 pandemic under then-premier Muhyiddin Yassin’s administration, Malaysians were riled up by what they perceived as constant flip-flops in regulations.

These included work-from-home guidelines and what products grocery and convenience stores could sell during the lockdown.

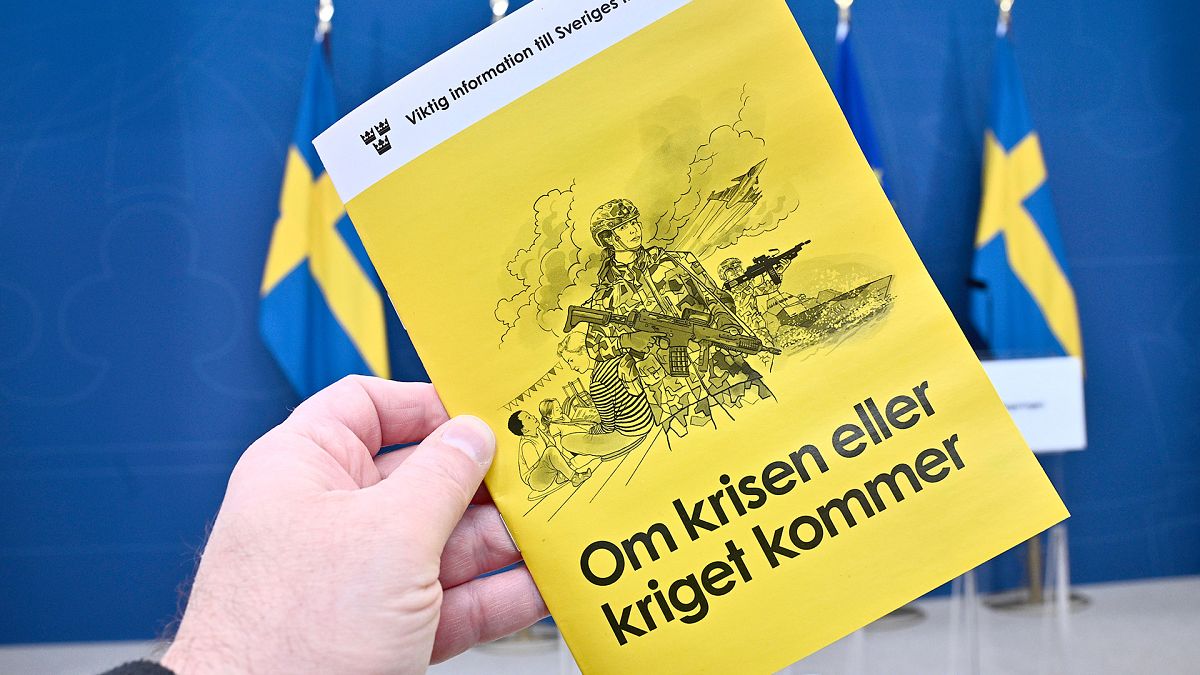

Prof Said Bani said the more recent reversals create a perception of inconsistency in policy execution and transparency, affecting public confidence in digitalisation efforts.

“From a communication perspective, these U-turns can be seen as reflective of a reactive approach, which may suggest to the public that there is a lack of coordination and clarity within the government’s policymaking process,” he said.

“The public may question whether due diligence and comprehensive planning are being consistently applied, particularly when policies are introduced and then swiftly reversed.”

WHY U-TURNS HAPPEN

The common theme in policy U-turns, Dr Ong said, is that the policymakers are not “hands on and minds on” enough when it comes to policy design and execution.

“A policymaker who has this kind of understanding will ask for proof of concepts, pilot project rollouts and stress testing before such policies are implemented to a wider public, especially in areas which can potentially affect a larger number of users,” he said.

Mr Asrul Hadi highlighted that this issue has persisted across different Malaysian administrations, which have launched “grand blueprints” that were not effectively translated to civil servants who are expected to implement the policy.

“Additionally, there is criticism regarding the lack of active engagement with the industry and the public when implementing policies,” he said.

“This has resulted in a lack of foresight on potential public backlash and unsatisfactory policy implementation, leading to reversals or U-turns by the federal government.”

Read the full article here