SpaceX launched its huge Super Heavy-Starship mega rocket on its seventh test flight Thursday, successfully “catching” the first stage booster back at its firing stand but losing its new-generation Starship upper stage spacecraft, which apparently broke up as it was reaching space.

Telemetry from the Starship froze eight minutes and 27 seconds after launch following unexpected engine shutdowns or failures. SpaceX later confirmed the ship’s destruction in a posting on X, using a tongue-in-cheek description:

“Starship experienced a rapid unscheduled disassembly during its ascent burn. Teams will continue to review data from today’s flight test to better understand root cause. With a test like this, success comes from what we learn, and today’s flight will help us improve Starship’s reliability.”

SpaceX

“We (lost) all communications with the ship,” a SpaceX launch commentator said of the Starship. “That is essentially telling us we had an anomaly with the upper stage.” A moment later, he confirmed: “We did lose the upper stage.”

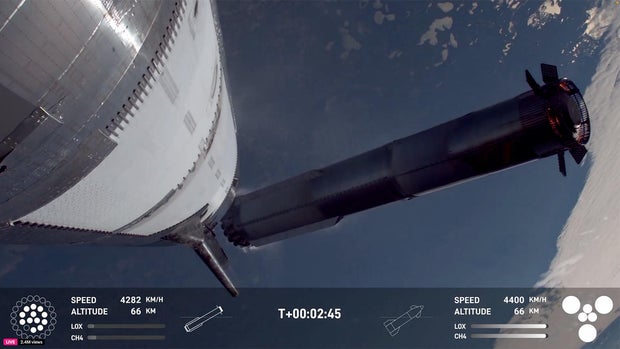

The gargantuan rocket blasted off from SpaceX’s Boca Chica, Texas, manufacturing and flight test facility on the Gulf Coast at 5 p.m. EST, firing up 33 methane-burning Raptor engines generating up to 16 million pounds of thrust.

Gulping 40,000 pounds of propellant per second, the booster climbed away from its launch stand and gracefully arced over to the east atop a long jet of flaming exhaust visible for dozens of miles around.

Two minutes and 40 seconds after liftoff, the Super Heavy fell away and the Starship continued the climb to space on the power of its six Raptor engines.

SpaceX

The booster, meanwhile, flipped around, re-ignited several engines to reverse course and headed back toward Boca Chica where the unique mechanical arms on the rocket’s launch gantry were open and waiting.

Plummeting tail first back to Earth, the Super Heavy re-ignited its engines, tilting as they steered it to the pad, and then settled straight down between the chopsticks, which smoothly closed to capture their quarry in mid air.

The first such catch last October was successful, a jaw-dropping sight to thousands of cheering residents and tourists. But the Super Heavy used for the next such flight a month later was diverted to a Gulf of Mexico splashdown because of launch damage to sensors on the tower that were needed to help guide the descending booster into position.

New sensors with have more robust shielding were put in place to eliminate such damage and SpaceX engineers are optimistic they’ll soon be recovering Super Heavy boosters with the same regularity they’ve demonstrated with the company’s workhorse Falcon 9 rockets, a key element in SpaceX’s drive to lower launch costs.

In keeping with the reusability theme, the Super Heavy’s 33 Raptor engines included one that flew on a previous test flight to demonstrate its ability to fly multiple missions.

The bulk of the upgrades tested Thursday were built into what SpaceX called a “new generation” Starship. Two minutes after the booster “landed,” the upper stage reached space.

SpaceX

SpaceX

But the loss of telemetry left flight controllers in the dark about what might have happened in the final stages of the ascent.

For these initial test flights, the Starships do not attempt to reach orbit. Instead, they loop halfway around the planet and descend belly-first through a hellish blaze of atmospheric friction before flipping nose up for a tail-first, rocket-powered splashdown in the Indian Ocean.

For Thursday’s flight, major test objectives included restarting a Raptor engine in space and the deployment of 10 dummy Starlink mockups to test a new satellite delivery system that works a bit like a Pez candy dispenser. Starships are expected to launch thousands of Starlinks after the rocket is operational.

Among the other upgrades were smaller stabilizing fins, repositioned to reduce their exposure to re-entry heating, an improved propulsion avionics system, redesigned fuel feed lines and a 25% increase in propellant volume to improve performance.

SpaceX

The redesigned avionics system includes a more powerful flight computer, new antennas that combine signals from Starlink and GPS navigation satellites, “smart batteries” and power units to drive two dozen high-voltage actuators and redesigned navigation sensors.

SpaceX also added additional cameras, with more than 30 on board to provide direct views of critical systems using operational Starlink satellites to stream real-time video and data to the ground.

While the spacecraft is designed to be fully reusable, SpaceX has not yet made any attempts to capture a returning Starship or, for that matter, a Falcon 9 upper stage.

But Thursday’s test flight featured multiple experiments to test a variety of heat shield improvements, including metallic tiles and one with active cooling, along with dummy Starship catch fittings, to learn more about how they will respond to re-entry heating.

“This new year will be transformational for Starship,” SpaceX said on its website, “with the goal of bringing reuse of the entire system online and flying increasingly ambitious missions as we iterate towards being able to send humans and cargo to Earth orbit, the moon, and Mars.”

Getting the Super Heavy-Starship flying on a regular basis is critical to NASA’s Artemis moon program. NASA is paying SpaceX to develop a variant of the Starship upper stage to carry astronauts down to the lunar surface in the 2027 timeframe.

To send a Starship to the moon, SpaceX must first launch it to low-Earth orbit where a succession of other Starship “tankers” will have to rendezvous, dock and autonomously refuel the moon-bound ship so it can blast out of Earth orbit and head for deep space.

Astronauts launched in an Orion capsule atop NASA’s Space Launch System rocket then will rendezvous with the Starship in orbit around the moon for the descent to the surface.

NASA’s contract requires one unpiloted lunar landing test flight before astronauts can be cleared to ride one down to the surface. The ongoing test program will determine when that might be possible.