Since PFAS were found in the south of Lyon, Pierre-Bénite has become a European symbol in the fight against forever chemical pollution.

But what are these substances exactly, and why are they causing concern across Europe?

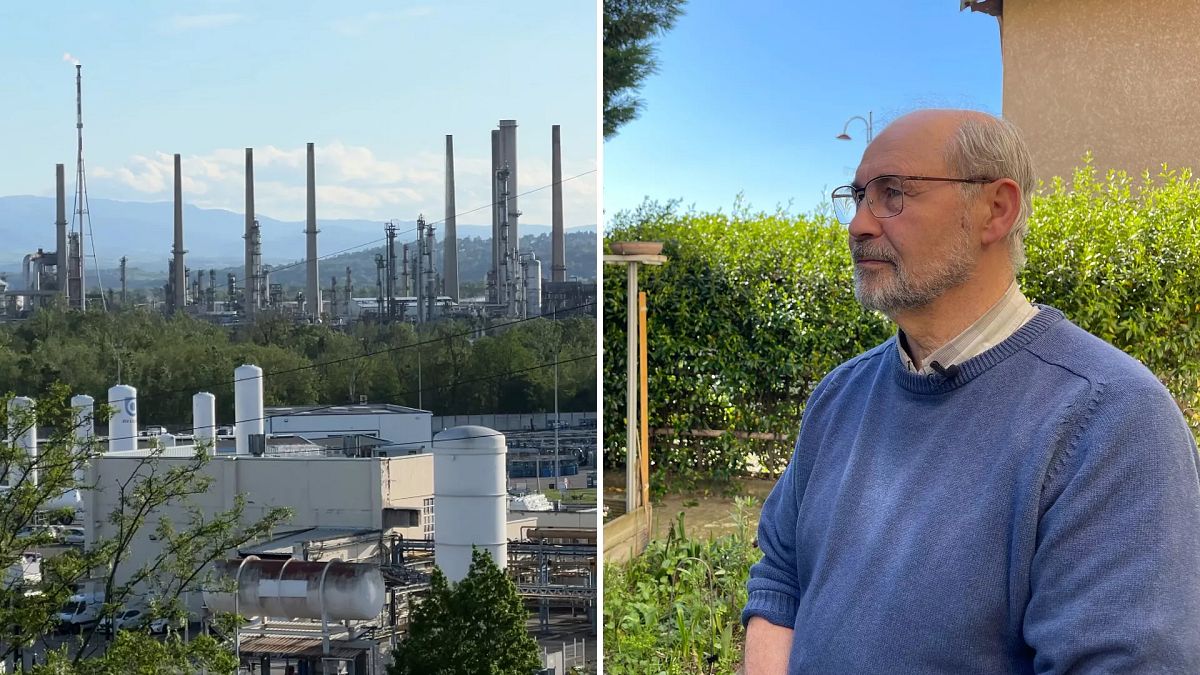

Thierry Mounib has lived in the French city of Pierre-Bénite for 70 years. Since childhood, he has enjoyed the tranquillity of the same neighbourhood while watching the area develop and welcome more and more industrial companies. He was always aware of the risks involved, but he never imagined that one day he would find himself at the centre of one of France’s biggest environmental scandals.

“I was presented with a fait accompli when the revelations about PFAS (forever chemicals) came out,” Mounib, the president of the association ‘Bien Vivre à Pierre-Bénite’ told Euronews.

In 2021, a journalist contacted him during a media investigation. The following year, the news broke: alarmingly high levels of forever chemicals were discovered in the water, soil, and air.

Two years after the revelations, Lyon’s metropolitan council has taken legal action against two chemical companies suspected of being responsible:the French firm Arkemaand the Japanese manufacturer Daikin. A judge recently ordered an independent expert report to assess the extent of the pollution and the companies’ liability.

According to Bruno Bernard, president of the metropolitan council, the next step is to apply the “polluter pays” principle, which would hold companies financially responsible for the environmental damage they cause. Activists hope this could set a precedent in France.

However, the inhabitants of Pierre-Bénite have a new concern: the resumption of operations of a new Daikin unit that produces and stores additive polymers for the automotive industry, some of whose components are forever chemicals. After halting production for four months, the extension of the company has been authorised under new rules imposed by the state.

What are PFAS exactly? And why are they raising concerns across Europe?

PFAS, short for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are a group of thousands of synthetic chemicals. They are called forever chemicals because they don’t naturally break down in the environment.

Scientific studies have detected these substances in the air, water, soil, animal feed, and even in human blood. Some PFAS are suspected of posing serious risks to human health, with research linking them to different types of cancers, cardiovascular and thyroid diseases, infertility, and immune system disorders, among other conditions.

These chemicalsare highly resistantand excel at repelling water, grease, and oil. As a result, they can be found in many everyday items, including food packaging, rain jackets, waterproof makeup, and dental floss. PFAS are also used to produce technologies that are key for the green and digital transitions, such as semiconductors, electric car batteries, and wind turbines.

Towards an EU ban on PFAS?

In 2024, the European Union decided to restrict a new subgroup of PFAS – PFHxA and its related substances – for some uses, including food packaging, cosmetics, and consumer textiles. However, only a few PFAS are currently banned at the EU level.

Today, all eyes are on a proposal submitted by five European countries in 2023. Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark, and Norway have called for a major restriction on PFAS under REACH, the EU’s chemicals regulation.

The European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) is currently evaluating the proposal. Once complete, it will share its opinions with the European Commission, which, together with the 27 member states, will decide on the restriction.

Watch our report by clicking on the player at the top of this article: you’ll find more information about PFAS, visit a controversial vegetable garden in Lyon, and watch an interview with ECHA’s Director of Risk Management, Peter van der Zandt.

Journalist • Natalia Oelsner

Video editor • Matthew Ashe

Additional sources • Marie Lecoq (Assistant producer)

Read the full article here