If you are a Western leader who has been on the receiving end of United States President Donald Trump’s mercurial decision-making, chances are you are considering a trip to Beijing.

The past two months have seen France’s Emmanuel Macron, Ireland’s Micheál Martin, Canada’s Mark Carney, Finland’s Petteri Orpo and Britain’s Keir Starmer make the journey to the Chinese capital. Germany’s Friederich Merz is expected to land later this month.

The official visits, largely focused on securing greater access to the notoriously restrictive Chinese market, coincide with a steady rise in transatlantic tensions caused by Washington’s ever-expansive foreign policy, including, most recently, an extraordinary attempt to coerce Denmark into selling Greenland.

The fracture in the alliance has not gone unnoticed by Chinese President Xi Jinping, who, every time he welcomes a dignitary, takes the opportunity to implicitly chastise Trump and portray his country as a staunch defender of multilateralism.

“The international order is under great strain. International law can be truly effective only when all countries abide by it,” Xi said during his meeting with Starmer, according to an official readout that also decried “unilateralism, protectionism and power politics”.

Beijing does little effort to conceal its ultimate goal: to drive a wedge between the two sides of the Atlantic and further expand its geopolitical clout to America’s detriment.

Western leaders have reacted positively yet cautiously to the overture, fearing an excessive display of enthusiasm might invite Trump’s wrath.

“It’s very dangerous for them to do that,” the US president said, referring to Starmer and Carney’s visits.

For the European Union, the balancing act is even more perilous. On the one hand, the 27-member bloc is desperate for new markets to compensate for the 15% duty agreed in a lopsided deal with Trump. China, as the world’s second-largest economy with a growing middle class, is on paper an enticing business partner.

But on the other hand, the EU is struggling more than ever to contain a ballooning trade deficit with China, as the country turns to low-cost exports to offset a stubborn real estate crisis and sluggish consumer demand. Beijing ended 2025 with a surplus worth almost $1.2 trillion (€1 trillion), the largest ever recorded by a nation in modern history.

The figure might have played a part in Macron’s defiant speech in Davos last month. Sporting an attention-grabbing pair of aviator sunglasses, the French president denounced China for its “underconsumption” of foreign goods and its “massive excess capacities and distortive practices”, which, he warned, “threaten to overwhelm entire industrial and commercial sectors”.

“It’s not being protectionist, it’s just restoring this level playing field and protecting our industry,” Macron said, as he called for greater “rebalancing”.

“Not an easy one”

In a way, Macron’s grievances encapsulate the last five years of EU-China relations.

Starting with the COVID-19 pandemic, a cataclysm that painfully exposed the bloc’s dependency on China-made basic supplies, European leaders began embracing, with varying degrees of conviction, a more assertive policy towards Beijing.

The posture further hardened after Russia launched the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Europeans were aghast at seeing Xi Jinping reaffirm his “no limits” partnership with Russian President Vladimir Putin and sustain his war economy. Soon, the circumvention of Western sanctions through Chinese territory became a major irritant.

“You cannot say that you’re a trusted, reliable partner for the EU if, at the same time, you enable our biggest security threat,” said a senior diplomat, speaking on condition of anonymity. “On the one hand, we need to partner with them for certain issues. On the other hand, they are fuelling a war of aggression. It’s not an easy one.”

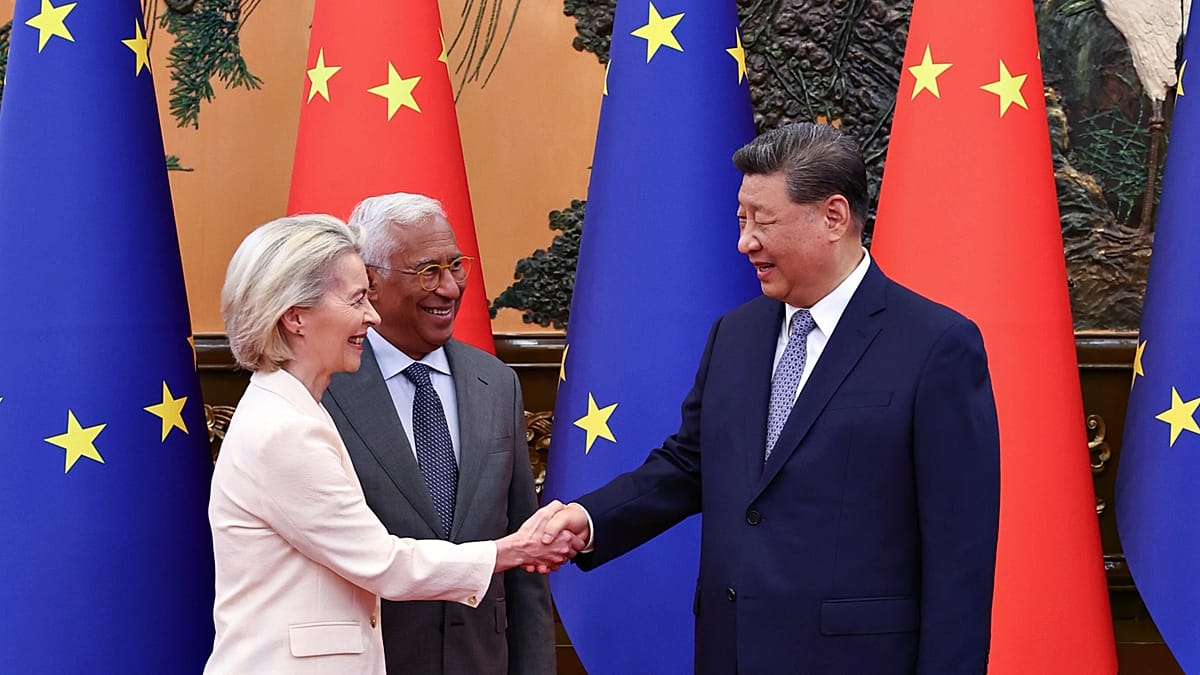

Amid sky-high tensions, Ursula von der Leyen, the president of the European Commission, coined the term “de-risking” to decrease security vulnerabilities with China and launched several probes into China-made products suspected of unfair competition, notably electric battery vehicles. The administration of US President Joe Biden cheered the moves and urged Europeans to close ranks and pile pressure on Beijing.

But then, Trump was re-elected, and everything changed overnight.

European officials assumed the economic challenges posed by China’s state-driven economy, which Trump openly denounced during his campaign, would serve as the political glue to keep both sides of the Atlantic somehow aligned. Trump, however, never settled on a consistent policy to deal with China, alternating between confrontation, conciliation and praise at a pace that baffled European capitals.

In the aftermath of Trump’s “reciprocal tariffs”, enraged European leaders softened their rhetoric on China and fuelled speculation of a diplomatic reset after years of clashes.

“We remain committed to deepening our partnership with China. A balanced relationship, built on fairness and reciprocity, is in our common interest,” von der Leyen said in May as she exchanged messages with Xi Jinping celebrating the 50th anniversary of relations.

But hopes of a reset were dashed when Beijing, as part of its confrontation with the White House, imposed stringent restrictions on the exports of rare earths, the metallic elements that are crucial for advanced technologies. The country commands roughly 60% of global production and 90% of the processing and refining capacity.

The curbs had a crippling effect on European industry, with some factories forced to limit working times and delay orders. The outrage was immediate: von der Leyen assailed China for its “pattern of dominance, dependency and blackmail”.

The Commission chief flew to Beijing in July for a pared-down EU-China summit that produced a preliminary breakthrough to ease the supply of rare earths. The agreement, which never fully solved the crunch for domestic companies, fell apart in October when Beijing, in yet another shock move, broadened the controls on rare earths.

Von der Leyen urged dialogue, to find a solution but warned: “We are ready to use all of the instruments in our toolbox to respond if needed.”

The Commission, though, refrained from hitting back. The EU’s Anti-Coercion Instrument, the so-called “trade bazooka” that was designed with China in mind, was never put on the table for a serious discussion. Sidelined and adrift, Europeans watched as Trump cut a deal with Xi to lift the restrictions, which benefited all countries worldwide.

Out of caution

The dispute over rare earths left Europeans with the bitter realisation that, for all their talk about “de-risking”, they will remain at the mercy of a chokepoint for the foreseeable future.

The Chinese leadership has proven willing to turn the restrictions on and off according to its foreign policy goals, raising serious concerns of weaponisation. The prospect of fresh controls has dampened Brussels’ resolve to pick up new fights with Beijing, at least for now – and while Macron is explicit with his complaints, others prefer to tiptoe.

At this year’s World Economic Forum in Davos, von der Leyen made only one reference to the country in her keynote speech, a remarkable contrast with her 2025 intervention, which devoted an entire section to what she called the “second China shock”. Like von der Leyen, Merz mentioned China just once in his Davos speech.

The same circumspection has marked the recent round of high-level European visits to Beijing. Escorted by hand-picked business representatives, the leaders put fractious political issues on the backburner in favour of commercial opportunities.

According to Alicia García-Herrero, a senior fellow at Brussels-based think tank Bruegel, these engagements need to be understood in the context of the shockwaves sent around the world by Trump, whose actions have offered China an invaluable opportunity – and spared the country the pressure of making tangible concessions to mollify outsiders.

“Everybody is flocking to China because they really fear the US, and that has to be understood,” García-Herrero told Euronews. “The ‘de-risking’ was something that happened during Joe Biden, but everybody knows the US is not ready to offer any carrots for ‘de-risking’, only sticks, whether you ‘de-risk’ or you don’t.”

“Notwithstanding the criticism of Trump, the Europeans are not ready to jump towards China, because they still think China is the usual thing: enabling Russia, doing nothing on industrial overcapacity, and imposing export controls on European companies.”

The back-to-back visits, which Brussels insists are coordinated, highlight one fundamental trait that has long characterised EU-China relations: disunity.

Since the 27 member states cannot agree on a common policy to handle the Asian giant, they each conduct diplomacy with it on a bilateral basis to pursue interests that at times diverge. These divergences hinder strategic discussions and blur long-term thinking at the European end. EU leaders have effectively stopped addressing China as a singular item when they meet in person for high-level summits, and foreign ministers do so only occasionally.

Still, the challenges persist, as China’s €1 trillion trade surplus demonstrated.

“China is posing a long-term challenge because it is using economic coercive practices towards our markets. We need to have a response to that,” High Representative Kaja Kallas said last week, making the case for trade diversification.

In Brussels, hopes for positive change are low. When the European Commission announced a procedural step in the row over subsidised electric vehicles, it was forced to tone it down after the Chinese side hyped it up as a breakthrough.

The Commission is expected to blacklist more Chinese entities accused of circumvention in the next round of sanctions against Russia, a stark reminder of how far apart both sides remain when it comes to the war in Ukraine, which Beijing still calls a “crisis”.

After the bruising ups and downs of last year, Europe’s 2026 will be defined by a difficult balancing act: to strengthen European economic security in the face of the US and China, while trying not to “rock the boat too hard”, says Alicja Bachulska, a policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

“Europeans seem paralysed in the face of challenges to their security – both hard and economic – emanating from both Beijing and Washington, so the appetite to make bold, and potentially costly, decisions is limited,” she told Euronews.

“Meanwhile, the clock is ticking, and Europe should understand that there will also be costs of inaction vis-à-vis Beijing, such as creeping de-industrialisation and even further dependence on value chains dominated by China.”

Read the full article here